England women’s team, 1924. Hilda Light (captain) is centre of the front row.

This image and all imagery in this article from the Hilda Light Collection, the AEWHA Archive at University of Bath Library.

The rapid evolution of women’s hockey after the Great War (1914 – 1919) from a regional and national sport into an internationally hosted and organised global sport by 1939 is one of the all-time sporting success stories. Between 1919 and 1939, while the world would decline into an economic depression and then a new global conflict, women’s hockey and the All England Women’s Hockey Association (AEWHA) with its steadfast belief in ‘amateurism’ would blossom. After the Second World War (WW2) women’s hockey continued to flourish along these lines into the early 1970s. It is during this time a number of individuals would play and administer hockey influencing its direction for the next 40 to 50 years. Important individuals of this generation such as Marjorie Pollard, Helen Armfield, Edith Thompson and Joyce Whitehead became influential leaders in the sport.

One name that stands out of this impressive line-up is Hilda Mary Light. Considered an excellent hockey player and captain of England, she was also a stalwart administrator of the AEWHA during its expansion phase of the 1920s and 1930s. She was also the archetypical governor of the international branch, the International Federation of Women’s Hockey Associations (IFWHA), as it became a global organisation after WW2. Hilda built upon her predecessors’ work and saw women’s hockey reach its absolute peak as a high amateur team sport. In many ways Hilda M Light dominated the direction of sport, never letting go of the principles of ‘amateurism’ and high standards that were set by the early-nineteenth-century pioneers. Her accomplishments and presence lasted for some 40 years, especially on the international scene. A true amateur sportswoman at heart, she embodied the spirit that defined hockey for much of its modern existence.

Hilda Mary Light was born on 6 September 1890 in the village of Pinner, sharing her birthday with her mother. Her father was a solicitor with the chambers in London, while her mother was an early member of Pinner Hockey Club. Light grew up in a stable, middle-class environment of the late Victorian age, with her elder brother Donald and younger sister Elise. Donald was himself a skilful hockey player, going on to play for England and later becoming Honorary Secretary of the Hockey Association (HA). From the start, and not uncommon with other hockey representatives, family was an important factor in providing emotional support, encouragement and an environment to foster a love of hockey. In essence ‘the hockey family’ – a phrase still commonplace within hockey today and a source of great pride for the sport.

Cambridge University First XI, 1911. Donald O Light is seated far right.

Light attended senior school in 1902, where her seriousness for good behaviour, manners and following rules were fostered. The great advantage of South Hampstead was its extensive games and gymnasium. While Light may have taken her schoolwork seriously, this was matched by her sporting abilities. At school, she played hockey along with tennis, netball, rounders and fives, where her dedication shone through. While at school, she was also a member of Pinner Hockey Club alongside her mother, sister and brother. The importance of hockey to Light was reinforced in the family home but it also combined with her Christian principles of the sport being a form of joy, working together, and peace.

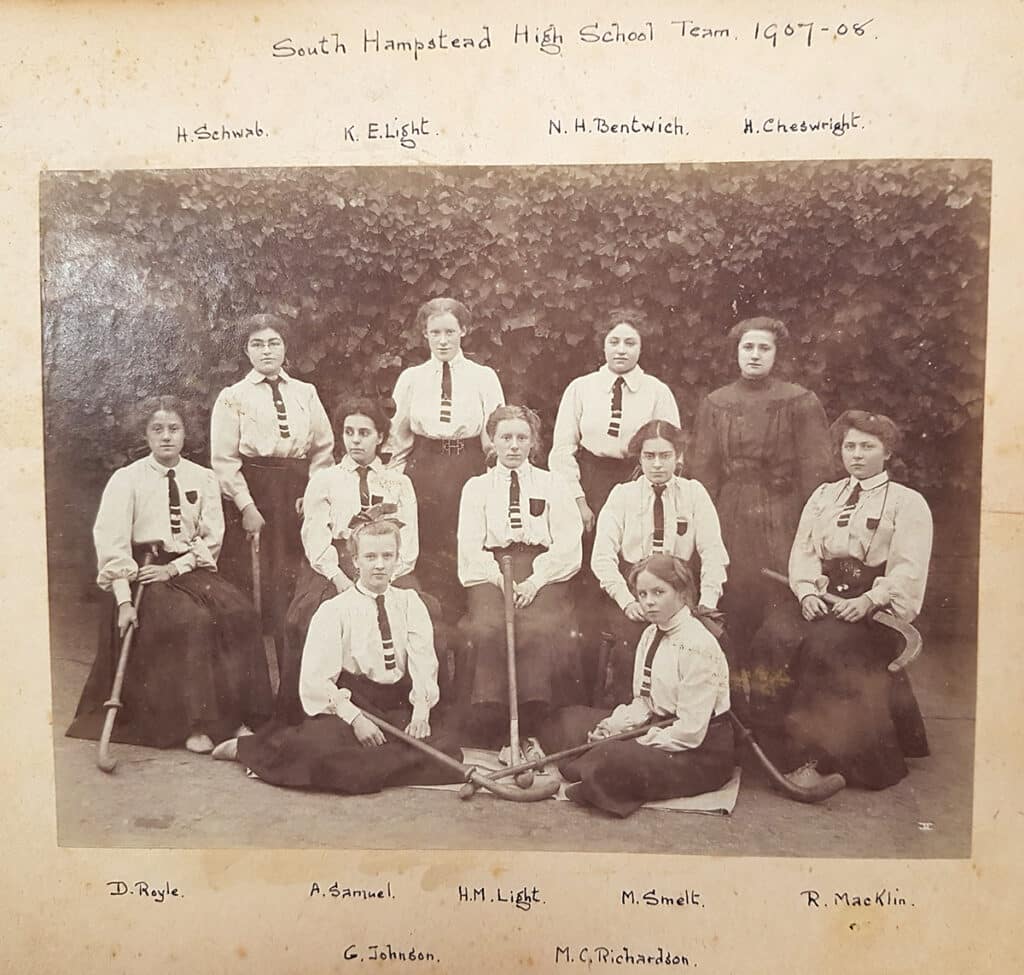

South Hampstead School, 1907, featuring Hilda (centre front) and her sister Elise (back row second left).

Pinner Hockey Club Ladies’ First XI, 1909. Hilda is seated second from right; her mother is seated far right.

After leaving school in 1909 Hilda would continue playing hockey for Pinner where she was quickly promoted to Middlesex County in 1912, joining Chiswick Ladies’ Hockey Club in 1913 followed by selection to the South territory team in the same year. In 1914 Light was called up to the English Reserves, but the outbreak of the First World War put hockey activities on hold for its duration. As was the way of her generation, Light volunteered for war service as a nurse with the St John’s Ambulance Brigade and later the Voluntary Aid Detachment in 1916. During this conflict Light played mixed hockey in her spare time with her fellow nurses, doctors and other branches of the wartime aid services. Here Hilda’s organisational abilities were demonstrated when she set up hockey matches.bric also make this flag fairly heavy, notably in comparison to the more lightweight cream fabric used for the flag’s ‘ground’.

Hilda as a nurse in WW1 (Hilda on the left).

The end of war saw the slow restart of the hockey activities, but Light quickly resumed her place with Middlesex First XI in 1919, then was selected to the South and England teams in 1920. Light played as a right half-back commanding a mix of playmaker with decisive passes and a stalwart of the defence. A personal achievement in 1924 was to captain her club, county, territory and country in the same year. It was also her last year as a player.

Hilda with the Welsh captain M Orsman during the 1924 International Tournament at Merton Abbey.

While Light was an avid player, she also had a career outside hockey. While the sport may originally have been for the leisured middle-class, by the early 1920s she took secretarial training at St James College and joined the wholesale booksellers and publishers, Simpkin Marshall, Hamilton Kent & Co Ltd as the head of the typing pool. Later she was promoted as private secretary to the Company’s Chairman. This was quickly followed by her acceptance of the secretarial position to the Associated Booksellers of Great Britain. Uncompromising in her duty towards the benefit of the booksellers, she pursued her Christian beliefs into the workplace.

While her representative playing career was relatively short, Hilda was elected South president in 1922 whilst playing for the same territory. They had previously amended their constitution so that she had a seat on the South Council as the South captain. Between 1922 to 1931 her presidency saw the South greatly expand in terms of membership and organisational structure; many of the international players of the time coming from her territory.

Hilda (centre) playing for the South.

Light’s rapid rise from player to captain and then president of a territory was an impressive achievement by any standards. This was further reinforced by her then being elected president of the AEWHA in 1931. She resigned as South president to take the post but retained a seat on the South Council until 1969.

Light was president of the AEWHA between 1931 to 1945, and her authority and influence was felt within and outside of the administration. She guided hockey into its new and growing international presence, while the sport’s national club and social membership also increased. Throughout the 1930s, she oversaw a number of important developments. In 1934 there was greater cooperation and affiliation with the trophy-playing, competitive northern leagues which had been a bugbear for the AEWHA since the 1910s. In 1938 the BBC commentated and broadcast the second half of the England vs Wales match at the Oval cricket ground. The introduction of an insurance scheme in 1935 was a way to help and safeguard the growing organisation, which by 1939, had 1207 clubs and 715 schools affiliated. Through this period Light held to the principles of the AEWHA founders with a strong adherence to amateurism. Perhaps a great example was when Scotland beat England for the first time in 1933, where she pointed out that while we play to win, there was relief that their (England’s) undefeated and onerous record had ended.

The start of WW2 once again put hockey activities on hold for the duration, although cooperation with women’s services and industrial clubs, and some representative matches organised in aid of charities continued. Hilda Light, as with the previous war, volunteered for war service as head of a warden post. In 1945 she retired as the AEWHA president, but for someone so dedicated to the sport she was not away for long. In 1950 she took up a new position as president of the IFWHA, an organisation formed in 1927 that she had been active with since 1931. The previous year, in 1949, she became a member of women’s Hockey Board of Great Britain and Ireland, remaining in the position until 1969.

The International Federation of Women’s Hockey Associations (IFWHA) Council. Hilda Light is front row, second from right.

The years after WW2 saw the rapid growth of IFWHA and international hockey with 20 affiliated countries by 1952. Her great achievement was to campaign to reverse the male-dominated International Hockey Federation’s (FIH) stance of non-affiliation of its members’ women’s sections with IFWHA. Light had sought to stop the split of women’s hockey on the world stage and this decision by the FIH in 1948 allowed IFWHA to become the leading federation for women’s hockey, creating a global hockey family.

The first IFWHA conference and tournament commenced in South Africa after WW2 in 1950. However, it was in the IFWHA Folkestone tournament in 1953 where the drive for a world sport was realised. In 1953 the new cooperation between the IFWHA and the FIH led to a Joint Consultative Committee. Hilda M Light became its first chairperson. She remained on the committee until her death.

The above points reveal that Light was dedicated to her sport perhaps above other considerations. There was a love, purpose and belief in the importance of hockey. Indeed, while keen on cooperation between women’s and men’s hockey, she followed the traditional line that administration of the game should be left separate to men’s and women’s representative organisations. After retiring from the position of the IFWHA president in 1953, she remained active in national administrations and at the international level. In 1955 she became president of Middlesex and continued as a member of the AEWHA rules and umpiring committee for a number of years. Her work with the International Federation was Light’s lasting legacy and her belief that it was a vessel for good in the world. She saw it as an instrument to bring women hockey players together in friendly competition and companionship, and a forum for ideas and viewpoints. Hilda M Light embodied these high ideals.

Hilda M Light died in 1969 after a lifetime of service in the sport. Perhaps fitting for such a dedicated servant of the game she died whilst on hockey affairs. Despite clearly being such an important and influential figure in world hockey, she has become a footnote in history, and her amateur vision of women’s sport would start to be replaced not long after her death. However, her lasting legacy was to see the expansion of women’s hockey through to its amateur peak in the 1950s and 1960s. She was pinnacle in creating a truly world federation of hockey nations that saw the dreams of her fellow early pioneers realised. In that, her legacy has persisted into the twenty first century.

David Lewis Early