Sir John Cecil Masterman was one of hockey’s D-Day heroes, not for efforts on the frontline beaches of Normandy, but for his valuable work for British Intelligence. He was the Chairman of MI5’s Twenty Committee, generally known as the Double-Cross Committee (XX Committee), in the lead up to the Allied landings on 6 June 1944.

Masterman was also an esteemed author, educator, and sportsman. Born in Kingston-upon-Thames on 12 January 1891, he was expected to follow in his father’s footsteps and therefore started his further education at the Royal Naval Colleges of Osborne and Dartmouth. Unexpectedly, he dropped out in 1908 to pursue a career as an academic. After studying Modern History at Worcester College, Oxford, he travelled to the University of Freiburg where he completed a postgraduate course and stayed in Germany to work as an exchange lecturer.

Following the outbreak of World War 1 (WW1) in 1914, Masterman found himself a British national behind enemy lines and was placed in a prisoner of war camp in Ruhleben, west of Berlin, on 28 November of that year. Masterman’s experience as a prisoner was tumultuous but it also provided opportunity. His 4-year capture and work as an exchange lecturer allowed him to perfect his German which would aid him in his future military career.

D-Day and the Twenty Committee

The start of World War 2 in 1939 meant that Masterman was promptly thrown back into the war effort. His fluency in the German language was a skill deemed especially useful and following his call up it earned him a spot in the Intelligence Corps. His role was focused on counter-intelligence within which he evidently flourished. After producing a thorough investigation into the evacuation of Dunkirk, he was awarded with a position in MI5 as a Civil Assistant. This in turn provided him with the opportunity to become the Chairman of the Twenty Committee, a group of British intelligence officials who were responsible for tackling counter-espionage, German spies, and the challenge of turning them into double agents. Masterman’s Committee would then organise and control what information would reach German intelligence, through their double agents, as a method of deception.

For the Normandy landings (Operation Overlord) to have the highest possible chance of success, British and Allied forces relied heavily on deception to mislead German expectations. Masterman and his Twenty Committee utilised their double-agent system in the deception plans of Operation Bodyguard, and its subpart Operation Fortitude. The goal was to deceive the Germans into falsely believing the Allies were to invade mainland Europe at Calais (the closest point between Britain and France) or German-occupied Norway rather than Normandy. An invasion of Calais from Dover was arguably too predictable and dangerous. The Allies needed to persuade the Nazi High Command to spread their defensive forces more thinly across multiple possible landing sites. The Twenty Committee’s double-agent system had a variety of different deceptive techniques that came into play. A large number of troops and equipment would have to concentrate in the launch area before an invasion. In order to deceive the Germans into thinking they were landing in Calais, the Allies set-up dummy formations and fake aircraft and landing craft around Dover to mimic authentic preparations and activity. Allowing German reconnaissance planes frequently close enough to view the fake formations or relying on a pretend leak from a double agent was thought to have been too obvious and predictable. Masterman’s role was to therefore provide his double agents with information on incredibly specific details like the types of vehicles and appearances of units stationed in the South-East. This worked in support of Operation Fortitude and its fake preparations, units, and formations by using double-agents to sell the story of a Calais invasion, spreading German defences away from Normandy. The double-agents’ detailed reports would then accurately reflect the information the Germans had gathered through their misdirected reconnaissance and their interceptions of fake Allied radio transmissions. All of this only further encouraged the plausibility of an attack on Calais.

MI5’s Double-Cross Committee proved effective. Between its start in 1939 and 1945 when it was finally disestablished, the Committee oversaw 120 cases of controlled enemy agents. The work of Masterman, his Committee, and agents, helped ensure a safer passage for British and Allied troops into France from where they would liberate Europe from Nazi tyranny.

Masterman’s Hockey Career

Back in November 1918 with the end of WW1, Masterman returned to Oxford where he became a tutor of his chosen subject Modern History. His life between the Wars saw a series of successes across sports and academia. He was particularly keen and skilled in tennis, golf, squash, athletics, cricket, and hockey. Masterman recalls in his autobiography his fondness for hockey specifically, which he describes as a “firmly and consistently amateur [sport]” attracting a “splendid” body of supporters and players. As an Oxford resident, with multiple colleges and county clubs to choose from, he joined the recently revived Oxfordshire County team. Here he became President of The Oxfordshire County Hockey Association and met the three Hartley brothers Richard, Ernest and Frank, who Masterman claimed to “form the backbone of the county hockey side”. (The Hartley Brothers and their Hockey Careers | Playing Pasts)

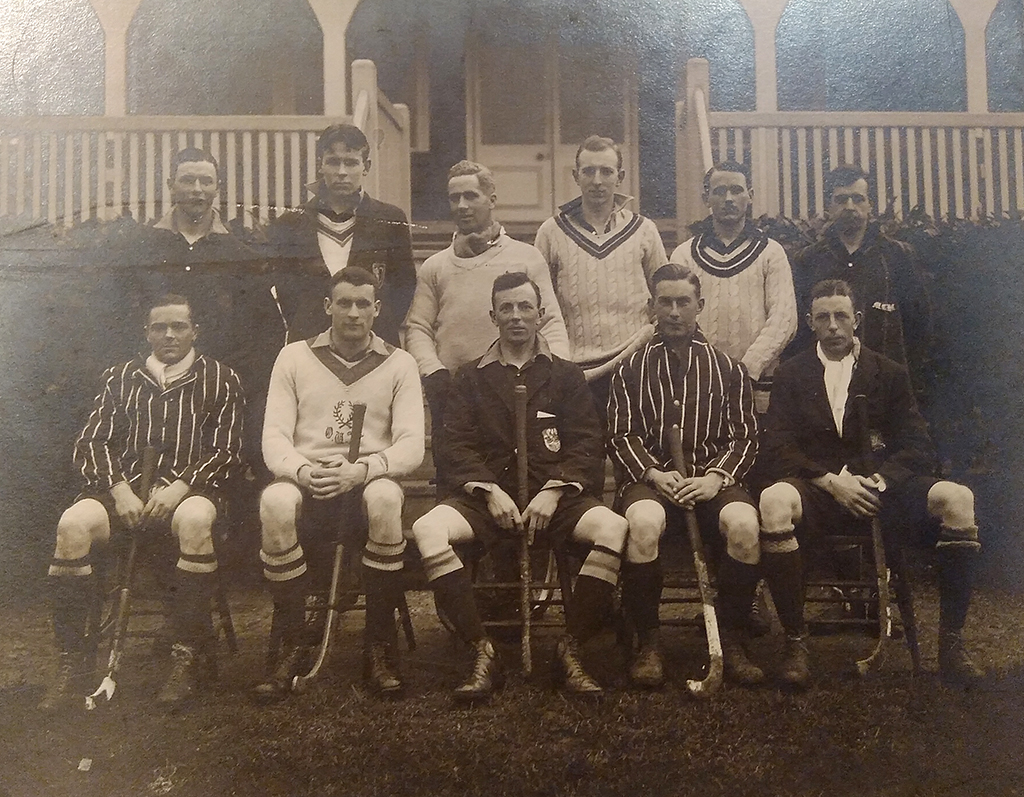

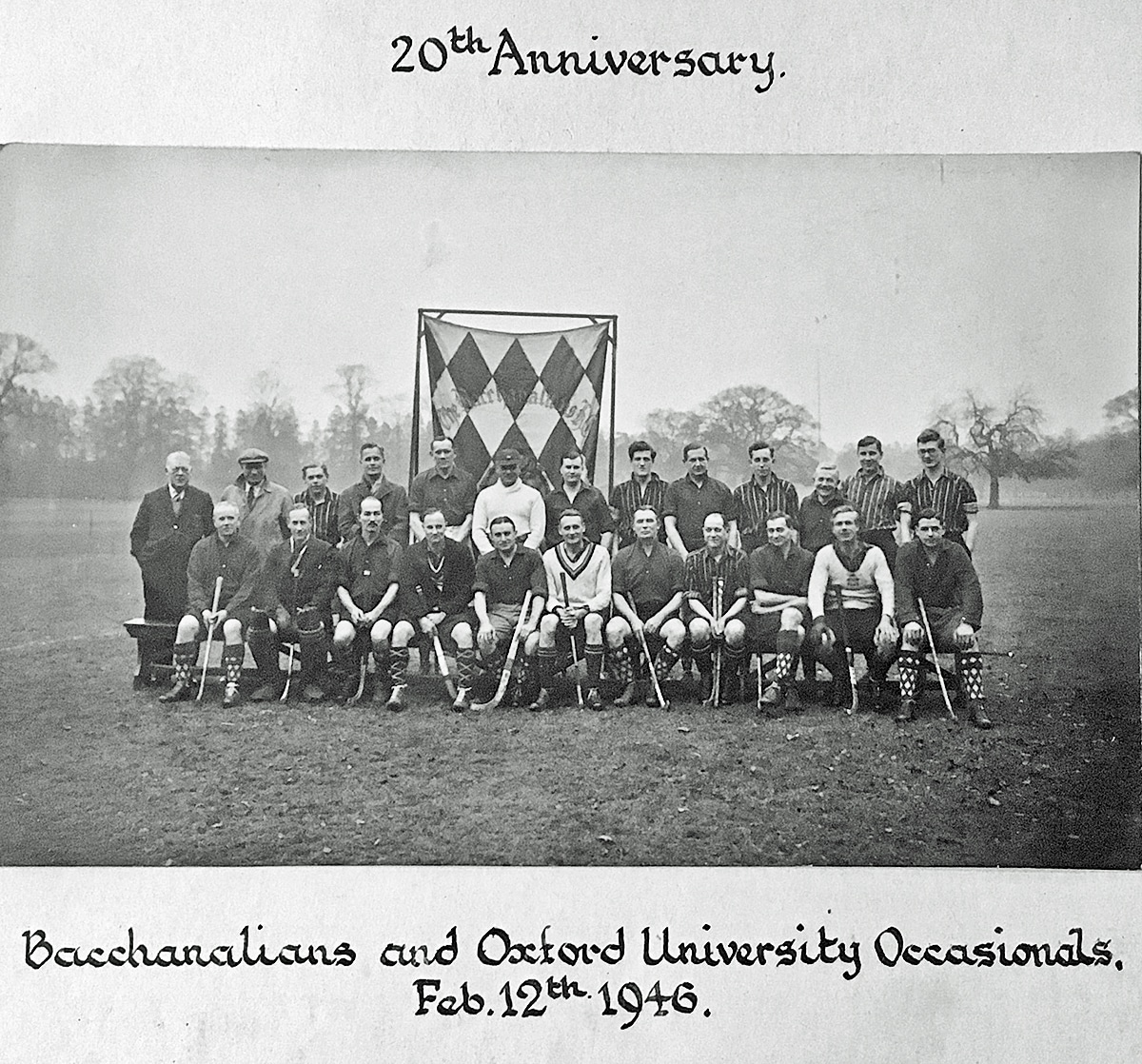

Masterman represented Oxford University Occasionals before and after World War 2. He is seated centrally wearing a white v-neck jumper in this photograph of the Bacchanalians and Oxford University Occasionals teams. Their match was in celebration of the Bacchanalians’ twentieth anniversary in February 1946.

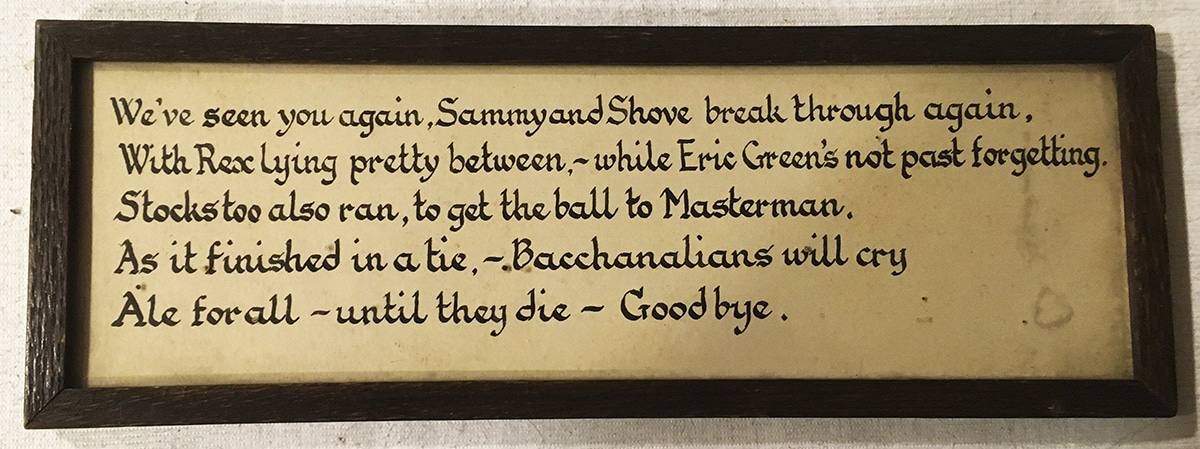

Masterman also played for Bacchanalians during his hockey career as evidenced by this calligraphed poem, presumed to be a drinking song given the teams enthusiasm for imbibing – their motto was “Ale for all”. The poem reads like a who’s who of amateur-era British hockey.

In 1923, with the Oxford University Occasionals hockey team, Masterman had joined a “prolonged” tour of Paris, Budapest, and Vienna which was reported to host a crowd of 2,000 spectators. Then followed a tour to France, Belgium, Germany, and Spain. Masterman is quoted in his autobiography that he particularly appreciated hockey during this time after the war, as he felt the sport “made a great contribution to better relations between countries and in this matter the Oxford University Occasionals were in the forefront”. The second Oxford tour ended with a festival in Barcelona in 1931 which Masterman described as “rivalling the lure of a bull fight – the crowd for their match against Terrassa was just as “large, noisy, and hostile”. He recalled a particularly tense moment between himself and a Spanish player in which one of their inside forwards hit his back foot and sent him crashing to the ground on two occasions. After noticing a bandage on the same player’s thumb, Masterman (playing at centre forward) pushed aside his own player to challenge the hostile player at the next bully himself. He recalls aiming his stick towards the “heavily bandaged” thumb, then taking a hit “and it was no light one”. The Spanish supporters protested and “all hell broke loose”. He was saved by a “stout hearted French umpire who persuaded the crowd to let the game continue”. Such competitiveness and strategic traits not only aided him in hockey but would serve him well in his future career with British counter-intelligence.

During an academic vacation period in 1925, he joined Hampstead HC which he was said to have enjoyed, however an irregular schedule meant his time with Hampstead was shorter than he’d hoped. Hampstead at the time had begun to attract multiple accomplished sportsmen and Masterman rubbed shoulders with some well-known names like Andrew Ernest Stoddart (English cricket and rugby) and Stanley Shoveller.

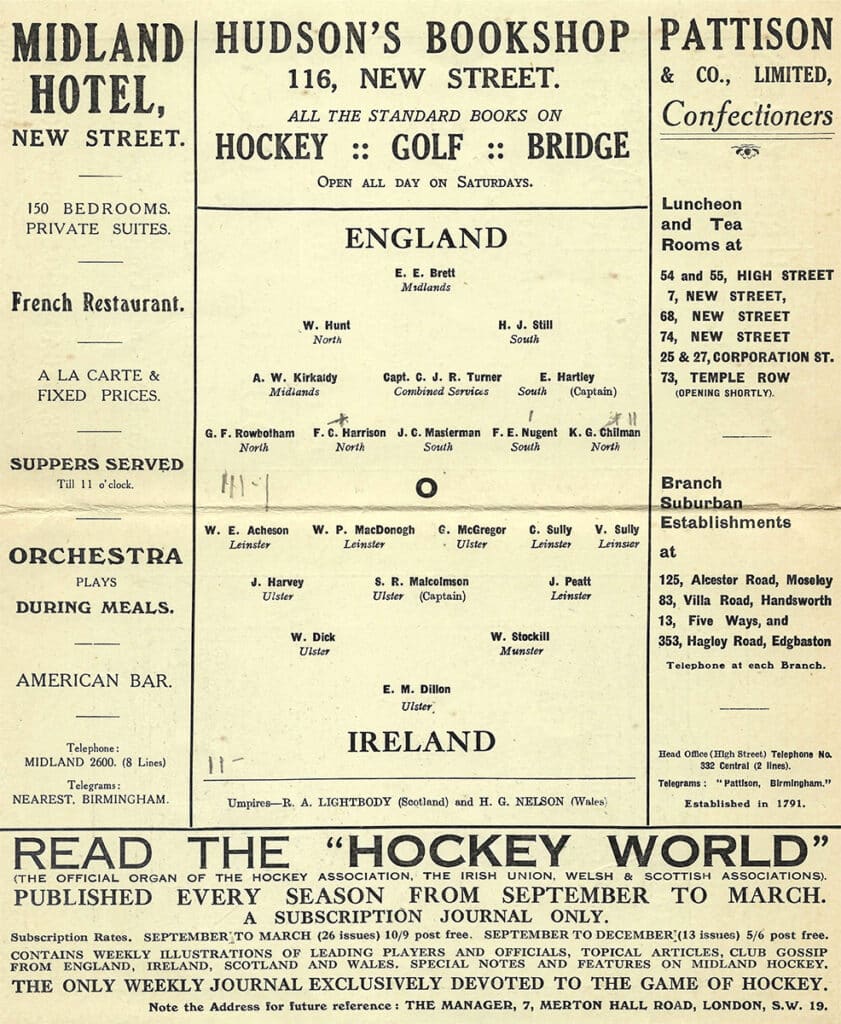

Whilst at Hampstead, Masterman was selected to play for England and would go on to earn four international caps during his career as an inside forward. England vs Wales on 9 March 1925 saw England score three goals within the first 9 minutes of gameplay. Second, came an England vs Scotland match on 16 March which ended with England winning 4-2. Masterman had scored twice, claiming the first goal of the game. England vs Ireland followed on 23 March. Despite reports of heavy snowfall at the start of the game, England pressed on and received another 4-2 victory. Masterman’s winning streak was met with a selection for the England vs France match in Paris on 4 April of the same year. He scored to help England earn a 5-0 win, however this game would be his last for a short period as in the spring of 1926 he contracted measles. Masterman would play again for England in 1927, but claims it was “poor consolation for the loss of 1926”.

“A W Woolley, who will lead the Rest forwards cannot be compared with J C Masterman, who, in his form in the Occasionals and Wanderers match, is about the best centre forward in England.”

5 January 1927 – Metropolitan Counties vs Rest match.

The programme for the England versus Ireland men’s hockey match at Edgbaston (Warwickshire County Cricket Club) on 21 March 1925. Masterman played centre forward and, whilst he didn’t score on this occasion, England triumphed 4-2.

Once the War had ended, Masterman wrote a book on the double-agent system. The Government’s Official Secrets Act created multiple setbacks for Masterman and 100 published books were immediately destroyed. After much determination, he successfully published his book overseas in 1945 forcing the British Government to abandon attempts to stop him. He went on to become Vice President of his much beloved Hampstead Hockey Club in 1950 and is noted as a key figure in the revival and regrowth of Hampstead after the war. Masterman was knighted for his wartime achievements and service in 1959.