Once the First World War had begun it became obvious that the Royal Navy, traditionally the pride of the British Nation for centuries, would have to play a vital role in what would become both a domestic and global conflict or perish in the attempt. Not for nothing is the Navy the Senior Service. Popular opinion had it, not without some good spin doctors and a jingoistic press, “that the British sailors, ships and know-how were simply the best.” Much of this may have inclined to the mythical but since Nelson and Trafalgar and Nelson’s fighting methods, the whole world believed it, not least the British – and probably more importantly – so did the Germans.

Once the First World War had begun it became obvious that the Royal Navy, traditionally the pride of the British Nation for centuries, would have to play a vital role in what would become both a domestic and global conflict or perish in the attempt. Not for nothing is the Navy the Senior Service. Popular opinion had it, not without some good spin doctors and a jingoistic press, “that the British sailors, ships and know-how were simply the best.” Much of this may have inclined to the mythical but since Nelson and Trafalgar and Nelson’s fighting methods, the whole world believed it, not least the British – and probably more importantly – so did the Germans.

At 14.00 on 31 May 1916 HMS Shark (below right), captained by Cdr LW Jones (right), was afloat with three other destroyers, Ophelia, Christopher and Acaster and two Light Cruisers. Commander Loftus William Jones came from a strong naval family, with both his father and uncle having been Admirals. He began his naval career in 1892 at the age of thirteen, serving on seven ships before being promoted Commander in June 1914 and taking command of HMS Shark in October of that year. No enemy ships were known to be in the vicinity and Shark’s Officers and men were relaxed, comfortable and rested, even after nearly two years of war.

On 31 March 1916 at 14.20, messages were received that enemy ships were now known to be in the vicinity and were on an intercepting course. The Ships Companies all went to action stations and the six ships proceeded at full speed to intercept.

On 31 March 1916 at 14.20, messages were received that enemy ships were now known to be in the vicinity and were on an intercepting course. The Ships Companies all went to action stations and the six ships proceeded at full speed to intercept.

At 17.20, three hours later, gunfire was heard. It was not known at the time but these sounds would signal the opening salvoes of the long-awaited battle between the two fleets. Within twenty minutes, ten German Destroyers and Light Cruisers arrived and launched their attack on HMS Hood’s Third Battle Cruiser Squadron. The four British Destroyers led by Jones broke up this offensive and they regrouped with the Canterbury and the Chester (of Boy Cornwell VC fame).

‘The six’ were then attacked by three German Battle Cruisers, intent upon ‘getting at’ the British Battle Cruisers. Under heavy fire, Shark was hit and a shell fragment destroyed the Bridge steering wheel. Jones ran down the Bridge ladder with his wounded Cox’n (Coxswain) and a Signalman, their one thought to get to the after Emergency Conning Position (ECP). On the way, when joined by Able Seamen Charles Smith, Charles Hope and Joseph Howell, another shell blew away the forward gun, laid waste the fo’c’s’le (forecastle), and killed all the forward gun’s crew but one. Another shell wrecked the Bridge. The Commanding Officer (CO) of one of Jones’s four destroyers, HMS Acaster, placed his ship between Shark and the enemy and once in hailing distance, a Leading Signalman presented the compliments of his Captain, Lt Commander John Ouchterlonie Barron RN and enquired whether Shark, “Would require any assistance?” Jones thanked him, presented his compliments to Lt Cdr Barron and replied that, “Barron should not put himself in danger/get himself killed (accounts differ) in order to help us.”

Enemy fire remained intense, it was obvious that their shells were full of shrapnel (the scourge of the hockey player Westmacott in 1914). Some struck Jones in the thigh and face, he was observed wiping the blood away with his hands. Petty Officer (PO) Cox’n William Griffin was hit again and was knocked unconscious. Jones sustained further damage to his leg and, as the Medical Officer had already been killed, he was ‘patched up’ by none other than the Chief Stoker. There had been two Chief Petty Officer (CPO) Stokers (Thomas Hamill and Frank Newcombe) on board, both did not survive.

As Hood and The Third Battle Cruiser Squadron increased speed, still on an essentially southerly course, Shark and company were left to their own devices. By now the after gun had been put out of action leaving only that amidships and the torpedo tubes.

The situation continued to worsen rapidly. The remaining crew were struggling to get away their final torpedo when the ‘tinfish’ itself was stuck as the crew were trying to load it and it exploded, killing and maiming even more of the depleted ship’s company and only leaving the ‘midships gun in commission.

Jones, from his position at the ECP was informed of further damage to the main engines and to steam pipes in the boiler room. Then Jones and the three Able Seamen (Hope Smith and Howell) went forward to man the ‘midships gun, Jones spotted the fall of shot. The situation was looking hopeless and he took the decision for surviving members to come up on deck to get collision mats in place and ready the life boats whilst he began to destroy confidential books and documents. There may have been a lull in German gunfire owing to a question in German minds, had Shark ‘struck her colours’, or just had them shot away?

Then, Jones’s leg was shot off above the knee.

Jones lay on the deck while two of his three lads tried to stem his bleeding whilst the other kept firing. He noticed that the Ship’s Ensign had been shot away, so he gave orders for a new one to be ‘bent on’. After this act of defiance, the ship was a fair target again in German eyes so their destruction of Shark was recommenced. The sailors continued to fire the ‘midships gun and as one of them fell Jones took his place.

At 19.00 Shark was sunk by a German torpedo. Two more were fired and only served to blow many of the men on life-rafts into the water. Of the ninety-one members of the ship’s company, twenty crew members had taken to the life-rafts and only six eventually survived to be picked up by a Danish ship, the SS Vidar, in response to a flare from a life-raft, and taken home to Hull later that night. According to those who survived, Jones was last seen clinging to a life-raft and encouraging fellow survivors to sing! However like many others, he succumbed to loss of blood, exhaustion and the cold and at some point slipped into the sea. Petty Officer William Griffin, who had been twice wounded in the attack, later recalled the scene. “On all sides there was chaos. Dead and dying lay everywhere around. The decks were a shambles. Great fragments of the ship’s structure were strewn everywhere”.

Whilst Jones and several life-rafted survivors were still alive, British Battle Cruisers swept past giving chase to the Germans. Honour restored! On being told, “They are ours”, Jones replied “That’s good”. Minutes later he lapsed into unconsciousness.

Cdr LW Jones’s medals. His Victoria Cross (far left) has a blue ribbon signifying his naval affiliation. This is one of the last times blue ribbons were used; thereafter VCs were awarded with purple ribbon regardless of military affiliation.

Cdr LW Jones’s medals. His Victoria Cross (far left) has a blue ribbon signifying his naval affiliation. This is one of the last times blue ribbons were used; thereafter VCs were awarded with purple ribbon regardless of military affiliation.

The Aftermath

Commander Jones’s Body was washed ashore on the Swedish coast. He still wore the Lifebelt that he had worn when being helped into the sea and on to a life-raft.

On 23 October 1916, his widow Margaret received a letter from The Admiralty informing her of the following – that on 24 June 1916, more than three weeks after the sinking – his body had been committed to a grave in Fiskebackskil, Vastra, Gotaland (Sweden) churchyard. His funeral had been attended by many local folk. Furthermore, a monument had been very quickly erected as a result of subscriptions from local fishermen. The ceremony had been marked with all due sympathy and reverence and this would be relayed to the British Public.

The story of Jones’s dedication to duty and his bravery would take a further six months to come out and the award of the Victoria Cross (VC) was not ‘gazetted’ until 6 March 1917.

Mrs Jones and her daughter Linette (then 6) had visited the grave and monument in Sweden before all remains were transferred, in 1961, to the British War Graves plot at Kviberg cemetery, Gothenberg, Sweden. She also had some of his personal effects returned to her. It was revealed that one of her husband’s last acts had been to say, “Let’s have a song lads”. Apparently one of the twenty on life-rafts (but not an eventual survivor) had been the First Lieutenant who had started singing, “Nearer my God to thee” (shades of Titanic, four years earlier).

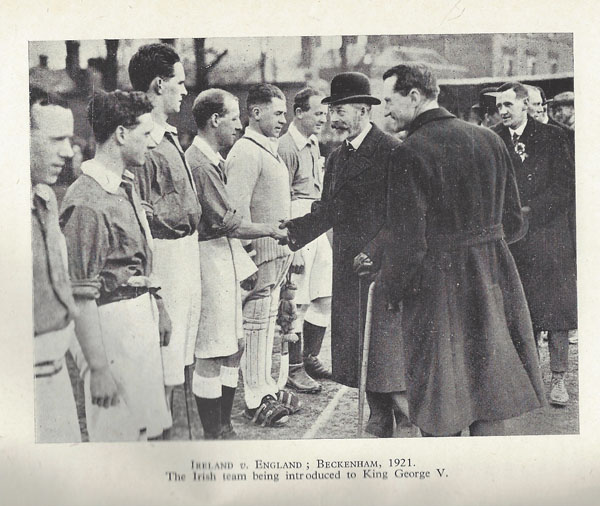

Mrs Jones received her husband’s VC from King George V at Buckingham Palace on 31 March 1917.

Lord Michael Ashcroft purchased Commander Jones’ VC and Service Medals in early 2014 along with his water stained wrist watch, smashed binoculars and the lifebelt he was wearing when he died. His VC and watch went on display at the Imperial War Museum in London.

Over the 100 years since the Battle of Jutland, countless thousands have marvelled at Jones’ Bravery, but only Royal Navy Hockey had any inkling of that other string to his bow – a hockey player who was a member of a cup winning team in 1902.

Alan Walker, July 2016