|

|

31.12.1923 – 25.5.2020

An Obituary Appreciation of Balbir Singh Senior.

By Nikhilesh Bhattacharya, THM volunteer.

Balbir Singh Dosanjh, who died aged 96 in Mohali, India on Monday, was arguably the greatest hockey player of the twentieth century.

A fearless, goal-poaching centre-forward par excellence, Balbir was an integral part of the teams from newly independent India that won the men’s hockey gold in three straight Olympic Games between 1948 and 1956. On the last occasion, in Melbourne, he stood on the podium as captain, just rewards for a man who always put the team above individuals. The rate at which he scored goals in that period was second to none.

What made Balbir even more remarkable was the fact that his contribution to Indian hockey went beyond his outstanding exploits on the field of play. After retiring as a player, he proved himself to be an astute coach and manager, and, for a while, he was the most perceptive observer of the game in India.

He was known as Balbir Singh Senior because as many as five younger players with the same name went on to represent India in international competitions. One of them, the 1968 Olympic bronze medal winner Balbir Singh Kullar, died after a heart attack in February 2020. However, as his name suggests, Balbir Singh Senior was always first among equals.

An articulate man, fluent in English, Hindi and his mother language, Punjabi, Balbir wore his laurels lightly and was humble to a fault. He was admitted to hospital with high fever and breathing difficulty on 7 May. He tested negative for Covid-19 but remained on ventilator support and later suffered multiple cardiac arrests, which left him in a coma.

Balbir was the recipient of Padma Shri, the fourth highest civilian award in India, in 1957. He was the first sportsperson to be honoured so. In 2012, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) included Balbir among sixteen iconic Olympians from across disciplines assembled for the London Games.

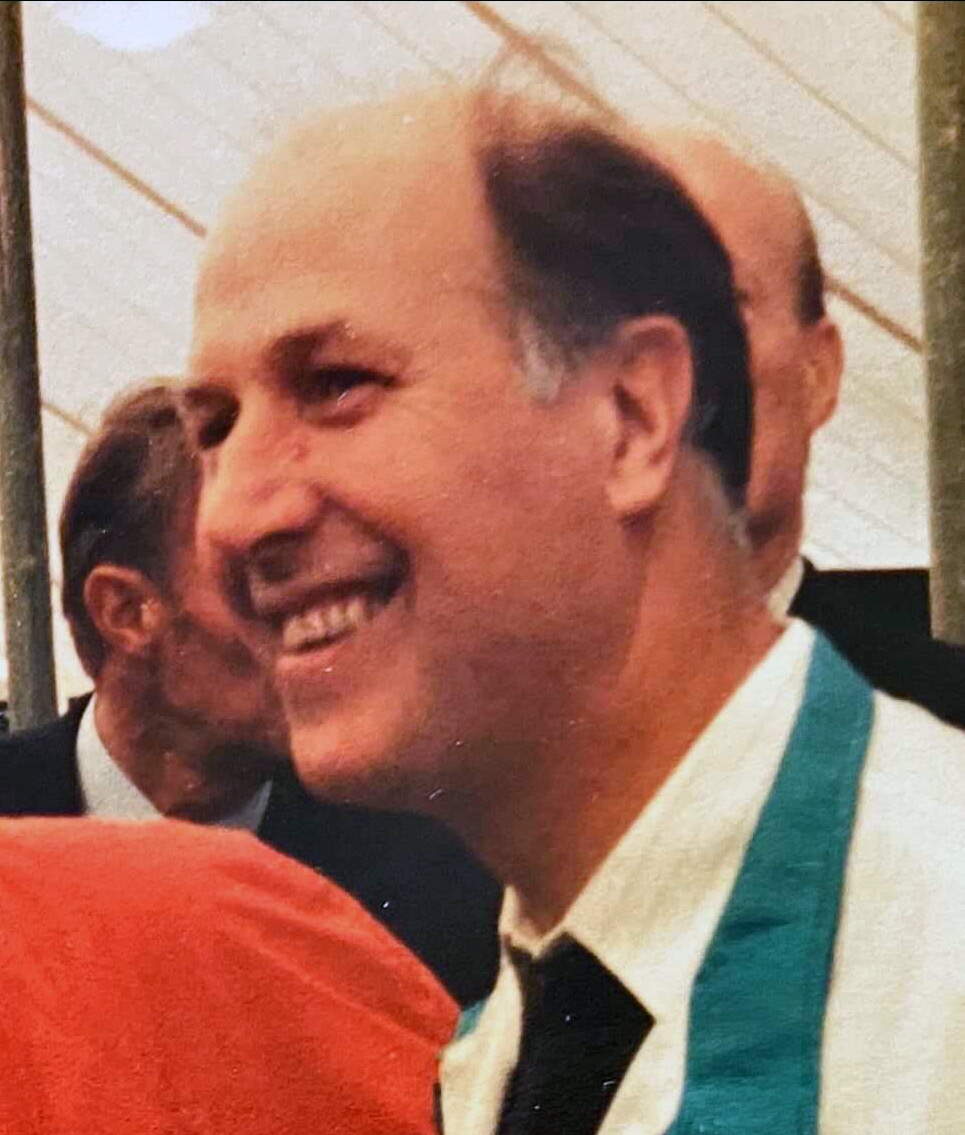

Balbir was a great friend and admirer of The Hockey Museum (THM). During his regular family trips between India and Canada he would break his journey in London and he visited the Museum several times. On his first visit in 2012, THM set up a meeting with John Peake, the Great Britain left winger in the 1948 Olympic Final against India in London. It was an incredibly emotional occasion, both for the two of them to meet again after 64 years and also for those of us who had the privilege to witness the meeting. The two genuine sporting gentlemen greeted each other with total humility and respect. Thankfully, the occasion was captured by ITV.

Balbir’s visits to the Museum felt like Royal occasions, such was the aura about him. He was always impeccably dressed, unassuming, kind and full of praise for the THM’s achievements.

|

John Peake and Balbir Singh Senior at The Hockey Museum in 2012.

Photograph: Dil Bahra.

Scoring When It Mattered

There had been legendary centre-forwards before Balbir, starting with Stanley Shoveller of England whose career spanned the first two decades of the twentieth century. The years between the First and the Second World Wars saw the emergence of a new star from undivided India, Dhyan Chand, dubbed the ‘human eel’ for his ability to evade opposition players. Dhyan Chand went on to win three Olympic gold medals with British India in 1928 Amsterdam, 1932 Los Angeles and 1936 Berlin, the last one as captain.

Like Shoveller, Dhyan Chand was a heavy scorer. So too was his brother, Roop Singh, an inside left who played with Dhyan Chand in two of those Olympic Games. Roop Singh once scored 10 goals in a 24-1 rout of the United States. And in the era of the astroturf, penalty corner specialists such as Sohail Abbas of Pakistan and Paul Litjens of Holland (who started on grass) have scored a glut of international goals. There have also been hockey players with more Olympic medals: Balbir’s teammates Leslie Claudius and Udham Singh both won one silver to go with three gold medals. And this is to say nothing about the women who have scorched the hockey fields since the end of the nineteenth century.

However, any estimation of Balbir must take into account the era in which he played. The larger context to his career was provided by a country recently freed from foreign rule trying to carry forward the hockey legacy of British India while also contending with a fledgling force in Pakistan. Independence on the Indian subcontinent came at a price. The partition of British India along religious lines left the two new nation-states of India and Pakistan scrambling to share the resources of the erstwhile colony. The situation was no different in hockey. Sometimes players felt compelled to switch allegiance leading to curious situations, such as when Akhtar Hussain won the Olympic gold with India in 1948 before migrating to Pakistan and going on the win the silver for his new country in 1956. Balbir was working in Punjab Police in 1947 and was an eyewitness to the terror unleashed by partition, about which he wrote in detail in his autobiography, The Golden Hat Trick: My Hockey Days, published in 1977. Like many Sikhs from both eastern and western Punjab, he decided to make India his new home.

The more immediate context was Balbir’s initial struggle to establish himself in the national side and later the pressure of being the talisman of a team burdened with the favourite’s tag. Three instances from the three Olympic Games in which he took part bear this out.

|

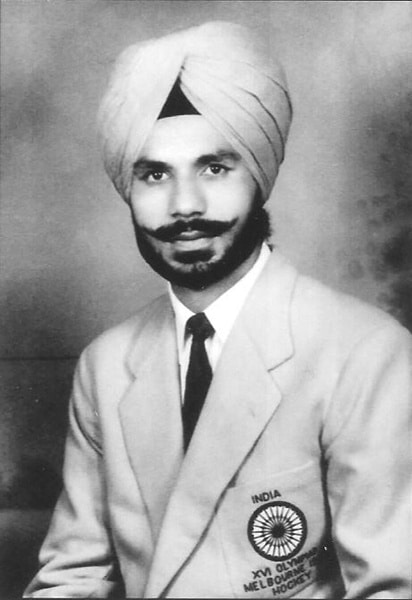

Balbir Singh, moments after scoring India’s first goal against Great Britain in

the final of the 1948 London Olympics at the Empire Stadium at Wembley.

In London in 1948, Balbir came into the final against the hosts having played in only one of India’s four previous matches in the competition. This despite Balbir scoring six goals in a 9-1 rout of Argentina. The team management’s decision to repeatedly bench him, including for the semi-final against Holland, rankled with Balbir for decades, though it was probably done to ensure each member of the squad got a game and thereby qualified for a medal (this was before hockey allowed substitutes). Whatever be the reason, at Wembley on 12 August 1948, before a record turnout of some 25,000 spectators, Balbir’s response was emphatic. On a ground heavy with rain and presumably unsuited to the Indian style of play, Balbir scored the first two goals as India defeated Great Britain 4-0. For young India, the win against the former rulers tasted especially sweet. However, Balbir also remembered the sporting nature of the home crowd: after the fourth goal, he recalled, even the English spectators in the crowd were egging India on to make it a half-a-dozen.

Balbir’s finest hour as a centre-forward came in the medals round of the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games, where he scored three out of three in the semi-final against Great Britain and five out of six in the final against Holland, the highest number of individual goals ever scored in an Olympic final. The 1956 Melbourne Olympic Games was a personal triumph as Balbir captained the side, scored five goals against Afghanistan in the opening game but also fractured his hand, and missed the next two matches. He ended up playing the semi-final and the final with the injury. He did not score in those two matches which India won by the identical score of 1-0, but his very presence on the field kept the opposition defenders occupied, thereby creating space for his teammates to exploit. The perfect team-man that he was, Balbir would not have begrudged the scorers, Udham Singh and Randhir Singh Gentle, their moment in the sun. It is the team that wins, he would always say.

Small Town, Big Dreams

Balbir was born in Haripur Khalsa village in Jalandhar district of eastern Punjab on 31 December 1923. (10 October 1924, which shaves off a year from his age, remains his ‘official birthday’, as Balbir had revealed in a Facebook post last October. His family had celebrated his 96th birthday on New Year’s Eve 2019.) Balbir’s father, Dalip Singh Dosanjh, was a freedom fighter who was often incarcerated, leaving Balbir to grow up with various relatives on his mother Karam Kaur’s side, claimed a recent biography of Balbir written in Punjabi. The father’s side of Balbir’s family traces its root back to the seventh-century Sikh warrior-preacher Bidhi Chand, the biography added.

Balbir’s hockey dreams started in the town of Moga, where his father was the hostel superintendent of the local school and the family lived in a rented house just a few yards from the hockey ground. As a young boy, Balbir would recall years later, he would play in any position as long as he was included in the team and in fact started as a goalkeeper. As his hockey skills improved, he moved up the field, ending up with the glamourous role of the centre-forward.

Balbir’s introduction to hockey in Moga proves how deep hockey had spread in British India, especially in the Punjab. However, for his career to take off, he needed to move to a bigger centre and it was failure that forced him to leave Moga. His love for hockey meant neglect of education and a failed examination in the local college left him with the unappetising prospect of repeating a year with his juniors. Relief came in the form of an invitation to join the Sikh National College in Lahore, with his hockey skills being the ticket. Later, he was spotted by Harbail Singh, the director of physical education at Khalsa College in Amritsar, and transferred to that institution. Just as Dhyan Chand had Bale (Bhole) Tewary, his first coach at the 1st Brahmins regiment of the British Indian Army, Balbir had Harbail, whom he called his guru. The word is loosely translated into English as teacher, though the last two elements of the expression friend, philosopher and guide probably come closer to its true meaning.

Harbail would later coach the national side at the 1952 and 1956 Olympic Games, Balbir recalled in his autobiography. The Indian Hockey Federation did not retain Harbail’s services for the 1960 Rome Olympic Games. Balbir was not picked for the tournament either, though he had been in the team that won silver at the 1958 Asian Games in Tokyo, losing out to Pakistan on goal difference. In Rome, India, captained by Claudius, lost to Pakistan in the final. Harbail died in a plane crash on his way back from Italy soon after the final.

Backroom Brains

After his playing career was over, Balbir continued to guide a new generation of players. By this time, he had quit his job in the police and joined the sports department of the Punjab state government. His finest hour in his new avatar came when he was the chief coach and manager of the Indian team that won the third Hockey World Cup in Kuala Lumpur in 1975. The captain of the team was Dhyan Chand’s son, Ashok Kumar, who scored the winning goal in the final against Pakistan.

Recalling the event in a post on his Facebook page two years ago, Balbir did not forget to mention the others who had worked with him on the campaign, right from the coach, Gurcharan Singh Bodhi, down to the yoga instructor, Dev Vohra, with a special mention of the players who executed the plans on the field. Balbir did not write about the personal sacrifices that he had had to make during the preparatory camp. His father had died while the camp was underway and his wife, Sushil, had taken seriously ill. Balbir had taken only a day off to cremate his father before going back to oversee the team’s preparations. After the team’s triumphant return to India, Sushil was at hand to receive Balbir and pose with him and the trophy for a photograph.

The Kuala Lumpur triumph remains India’s only World Cup win as international hockey shifted to artificial surface soon after and India struggled to come to terms with this seismic change. The country faced other challenges too, which included, but were probably not limited to, the government’s apathy to sports in general, the death of hockey in educational institutions, factionalism in the federation, regional bias in selection and the mass exodus from India of the Anglo-Indians, who had adopted hockey as their chosen sport.

Balbir was acutely aware of these challenges, which is one of the reasons why he wrote his autobiography in collaboration with journalist Samuel Banerjee two years after the World Cup win. In The Golden Hat Trick, Balbir lamented the fact that as a college student he was made to read about the exploits of Ranji (Ranjitsinhji, who played cricket for England and reportedly did little for the development of Indian cricket after coming back to rule over his native state of Nawangarh in western India) written by an Englishman (AG Gardiner) and not about Indians who shone on the hockey fields. Hockey players from the subcontinent had published books before Balbir’s attempt, notably MN Masood who wrote about British India’s triumph at the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games in 1937 and Dhyan Chand, whose memoirs were serialised in Sport & Pastime, a Madras-based sports magazine, between May 1949 and January 1951 before being collated and published as a book in 1952. However, Balbir’s autobiography, written in the form of “as told to”, was a far more detailed book and hinted at a new phase of literature on Indian sports (the cricketer Sunil Gavaskar’s autobiography, Sunny Days, was published a year earlier). Perhaps, Balbir had hoped that a new generation would be inspired by his book and take up hockey.

Unfortunately for Indian hockey, it did not pan out as Balbir had imagined. India continued to slip down the pecking order in international hockey, notwithstanding the gold medal in the largely boycotted Moscow Olympic Games of 1980.

Cricket, which had even deeper roots in the country despite the national team’s modest international record in the first 50 years of existence, took off after India won the world cup at Lord’s in 1983, followed by victory in the World Championship of Cricket in Australia two years later. When the government initiated economic liberalisation of India in 1991, the cricket administrators were the first ones off the blocks, working hard to commercialise cricket and thereby bring in money that could be invested back into the sport. Of course, the massive riches that fill the coffers of the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) today were still a couple of decades away, but their roots can be traced back to the early 1990s. Hockey, with its amateur ethos, was left far behind and remained largely dependent on largesse from the government, which had more pressing things to deal with than sport.

At Home In India

Meanwhile, Balbir himself moved to Canada where he lived with his three sons for a few decades. In his absence from the public gaze, the memory of his exploits faded from the Indian consciousness.

He was never completely forgotten. In 2004, Gulu Ezekiel and K Arumugam published a book containing biographical sketches of 22 great Indian Olympians and Balbir’s name was second on the list, after Dhyan Chand’s. In 2018, his legend attracted renewed interest from his countrymen following the release of a Hindi commercial film, Gold, a sensationalist retelling of India’s quest for the Olympic hockey gold in London in 1948.

Modern India has had a complex relationship with its past and preserving history has never been India’s forte. Even by these standards, it was shocking when reports emerged in 2016 that some of Balbir’s priceless memorabilia, which had been donated to the Sports Authority of India for a proposed museum, had gone missing. The sad episode was one of the rare things that made even the equanimous Balbir angry.

This kind of apathy towards Balbir’s achievements led Patrick Blennerhassett, a Canadian journalist, to write a new biography of the man, entitled A Forgotten Legend: Balbir Singh Sr, Triple Olympic Gold & Modi’s New India, in 2016. In it, Blennerhassett identified religious bias as the primary reason why Balbir was not as celebrated in India as Dhyan Chand, for example. Balbir, after all, belonged to the minority Sikh community in a Hindu-majority country.

Blennerhassett wrote the book after travelling to India and seeing Balbir’s anonymity first-hand, so there is no reason to doubt the veracity of his account. However, in looking for the real reason for the apathy, Blennerhassett may have underplayed the role of Balbir’s long absence from India. A contrary case in point is fellow Sikh and 1968 Olympic gold medal winner Gurbux Singh, who remains a celebrated hero in his adopted city of Calcutta. Since his return to India, Balbir, too, has received media attention from time to time. All media outlets in India covered extensively his last battle with illness even in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

While India could be accused of apathy towards Balbir, the opposite was never true. Even when he was living in Canada, Balbir was adamant that his heart always lay in India. Some six years ago, in a television interview shot during one of his visits to India, Balbir had said he would die an Indian. He kept his word.

Balbir is survived by daughter Sushbir, sons Kanwalbir, Karanbir and Gurbir, and grandchildren.

Balbir Singh Dosanjh, hockey Olympian, coach and manager, born 31 December 1923; died 25 May 2020.

Career At A Glance

Name: Balbir Singh Dosanjh

Also known as: Balbir Singh Senior

Olympic Record

1948 London: Gold; 8 goals in 2 matches, including 2 in the final

1952 Helsinki: Gold; 9 goals in 3 matches, including 5 in the final

1956 Melbourne: Gold (as captain); 5 goals in 3 matches

Other medals/cups

1958 Asian Games in Tokyo: Silver

1971 World Cup in Barcelona: Bronze (as coach)

1975 World Cup in Kuala Lumpur: Gold (as chief coach-cum-manager)

Awards/Recognition

1957: Recipient of Padma Shri, India’s fourth highest civilian award

2012: Included among 16 Iconic Olympians assembled by IOC for the London Olympic Games

Hockey Legend Balbir Singh Senior

A further appreciation of Balbir Singh Senior was penned by former The Hockey Museum’s Founder-Trustee Dil Bahra. Within it, Dil reflects on his personal relationship with Balbir and the treasured experiences they shared.

This document is available to view and download by clicking the PDF icon.